A Christmas carol

The first Christmas after her husband had passed away, the widow was paid an afternoon visit by the young married couple who lived across the quiet street. Youthful Santas, they came bearing gifts: conversation, a bottle of wine, and a book. The house became loud and jolly. The woman was cheered.The book they left was Christmas at The New Yorker, a compendium of Christmas stories, poems, and cartoons that had appeared in The New Yorker magazine over the years. Contributors included —posthumous and au courant— such as John Cheever, Garrison Keillor, Alice Munro, Ogden Nash, Calvin Trillin, E.B. White, Roger Angell, Brendan Gill, Ken Kesey, Vladimir Nabokov, James Thurber, and John Updike.

Later, in quiet, one of the stories the woman would read was Stare Decisis, written by H.L. Mencken, the cantankerous gadfly of the Baltimore Sun newspaper in the early 20th century. It told the Christmas adventure of a turn-of-that-century brewery salesman of Baltimore, Maryland. He was, as Mencken described him, a Tortsäuffer: "literally a dead-drinker, a brewery's customers' man. One of his most important duties is to carry on in a wild and inconsolable manner at the funerals of saloonkeepers."

**************

Stare Decisis

Despite all the snorting against them in works of divinity, it has always been my experience that infidels —or freethinkers, as they usually prefer to call themselves— are a generally estimable class of men, with strong overtones of the benevolent and even of the sentimental. This was certainly true, for example, of Leopold Bortsch, Tortsäuffer for the Scharnhorst Brewery, in Baltimore, forty-five years ago, whose story I have told, alas only piecemeal, in various previous communications to the press. If you want a bird's-eye of his character, you can do no better than turn to the famous specification for an ideal bishop in I Timothy III, 2-6. So far as I know, no bishop now in practice on earth meets these specifications precisely, and more than one I could mention falls short of them by miles, but Leopold qualified under at least eleven of the sixteen counts, and under some of them he really shone.

He was extremely liberal (at least with the brewery's money), he had only one wife (a natural blonde weighing a hundred and eighty-five pounds) and treated her with great humanity, he was (I quote the text) "no striker...not a brawler," and he was preëminently "vigilant, sober, of good behavior, given to hospitality, apt to teach." Not once in the days I knew and admired him, c 1900, did he ever show anything remotely resembling a bellicose and rowdy spirit, not even against the primeval Prohibitionists of the age, the Lutheran pastors who so often plastered him from the pulpit, or the saloon-keepers who refused to lay in Scharnhorst beer.

Mencken continued, with the saga of a gala —shall I say, huge— Christmas dinner for Baltimore's poor and homeless, "the masterpiece of a benevolent career, [...] a Christmas party for bums to end all Christmas parties for bums." [No hindsighted moral superiority, please.]

First and foremost, they wanted as much malt liquor as they would buy themselves if they had the means to buy it. Second, they wanted a dinner that went on in rhythmic waves, all day and all night, until the hungriest and hollowest bum was reduced to breathing with not more than one cylinder of one lung. Third, they wanted not a mere sufficiency but a riotous superfluity of the best five-cent cigars on sale on the Baltimore wharves. Fourth, they wanted continuous entertainment, both theatrical and musical, of a sort in consonance with their natural tastes and their station. Fifth and last, they wanted complete freedom from evangelical harassment of whatever sort, before, during, and after the secular ceremonies.

As in the wonderful 1990s flick, Big Night, the dinner does indeed go on.

It might have cost him his last cent if he had gone it alone, for he was by no means a man of wealth, but his announcement had hardly got out before he was swamped with offers of help. Leopold Bortsch pledged twenty-five barrels of Scharnhorst beer and every other Tortsäuffer in Baltimore rushed up to match him. The Baltimore agents of the Pennsylvania two-fer factories fought for the privilege of contributing the cigars. The poultry dealers of Lexington, Fells Point, and Cross street markets threw in barrel after barrel of dressed turkeys, some of them in very fair condition. The members of the boss bakers' association, not a few of them freethinkers themselves, promised all the bread, none more than two days old, that all the bums of the Chesapeake littoral could eat, and the public-relations counsel of the Celery Trust, the Cranberry Trust, the Sauerkraut Trust, and a dozen other such cartels and combinations leaped at the chance to serve. Even the ketchup was contributed by social-minded members of the Maryland canners' association, and with it, they threw in a dozen cases of dill pickles, chowchow, mustard, and mincemeat.

And it was grand. A bierabend!

A Bierabend, that is, a beer evening. Extra pitchers were put on every table, more cigars were handed about, and the waiters spread a substantial lunch of rye bread, rat-trap cheese, ham, bologna, potato salad, liver pudding, and Blutwurst.

Mencken was a cantankerous scribe of the early twentieth-century; he pilloried establishment figures, disfavoring businessmen, government, the middle class, and organized religion alike. So, again avoiding PC-ism, understand Mencken's peroration, as he bemoans how the benevolent Bierabend —of course and unfortunately— ultimately went awry.

I didn't see Fred again for a week. But the next day, I encountered a police lieutenant ["then the only known freethinker on the Baltimore force"] on the street, and he hailed me sadly. "Well," he said, "what could you expect from the bums? It was the force of habit, that's what it was. They have been eating mission handouts so long they can't help it. Whenever they smell coffee, they begin to confess. Think of all that good food wasted! And all that beer! And all them cigars!"

******************

And to all a good night

Stare Decisis was an H.L. Mencken Christmas carol. There never was a Scharnhorst Brewery. There were no Tortsäuffers or Bierabends. But how glorious if there would have been ... if today there would be.The merry widow? After reading this story, she bookmarked it as a fable she thought that I —then earning a living as a brewery's customers' man— might enjoy. She was my mother, since reunited with my father in the firmament.

This Christmas season, I re-discovered her handwritten bookmark. I turned to page fifty-eight of that book, as she had suggested long ago. And I read along, with a winter beer near at hand. It was a Bierabend of one.

Peace, happiness, and health to you, my readers. Don't waste your beer!

-----more-----

- Christmas At The New Yorker: Stories, Poems, Humor, And Art, was published in 2003. It is now out-of-print, but copies can be found online. Recommended.

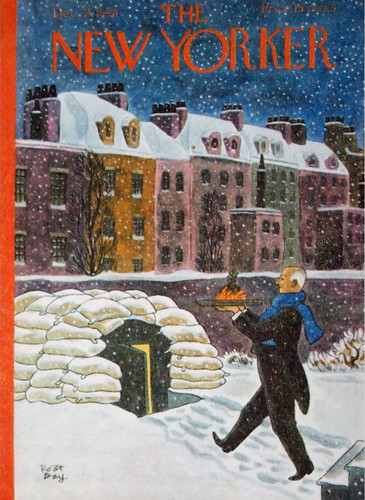

- The upper image was cartoonist Robert Day's illustration for the 21 December 1940 issue of The New Yorker; the lower, William Crawford Galbraith's for 14 December 1935. At the time, an issue cost fifteen cents.

- Stare decisis, from Merriam-Webster:

A doctrine or policy of following rules or principles laid down in previous judicial decisions unless they contravene the ordinary principles of justice.

- I Timothy III, 2-6, from the New American Standard Bible:

If any man aspires to the office of overseer, it is a fine work he desires to do. An overseer, then, must be above reproach, the husband of one wife, temperate, prudent, respectable, hospitable, able to teach, not addicted to wine or pugnacious, but gentle, peaceable, free from the love of money. He must be one who manages his own household well, keeping his children under control with all dignity (but if a man does not know how to manage his own household, how will he take care of the church of God?), and not a new convert, so that he will not become conceited and fall into the condemnation incurred by the devil. And he must have a good reputation with those outside the church, so that he will not fall into reproach and the snare of the devil.

- For more from YFGF:

- Follow on Twitter: @Cizauskas.

- Like on Facebook: YoursForGoodFermentables.

- Follow on Flickr: Cizauskas.

- Follow on Instagram: @tcizauskas.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comment here ...